Beginning in 2018 "Ruth's Neighborhood" entries were also posted on Ruth's FACEBOOK page where her entries (usually weekly, on Sunday mornings) lead to lively conversations.

This Page: 2008 -2011

2011

THE LOT

October 12, 2011

Back in the golden age of magazines, they published a great many short stories. And back then Cosmopolitan magazine was in its pre-Helen-Gurley-Brown heyday, with all its syllables pronounced and its pages filled with fiction—stories, serials, and ach month a “novelette.”

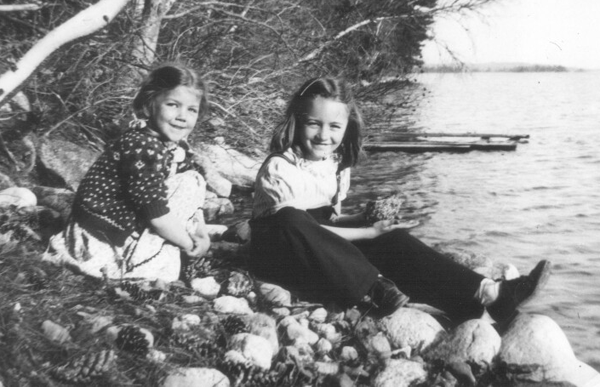

To the northwest around Lake Winnipesaukee from Laconia, in Moultonborough, out on Moultonborough Neck near the bridge to Long Island (not that Long Island!), a realtor had bought a chunk of lakefront woods and divided it into lots. Dan and Ernie were the first customers to buy a lot. I can’t remember its dimensions, if I ever knew, but because we were the only ones in that development, it had no boundaries. We felt as if the whole woods and lake were ours.

Nowadays the drive from Laconia to the bridge on Moultonborough Neck takes about forty-five minutes. Back then, on the old roads in the old pre-War gray Mercury, it must’ve taken at least an hour, probably more, and of course that seemed like forever to two little girls in the backseat squabbling over, amongst a multitude of things, who got to sit on the side that had the hand strap. Why that hand strap was so desirable escapes both Penny and me now, for we don’t think that whichever one of us was sitting on that side bothered to use it to keep from sliding across the seat when the car went around a curve—and thus came another squabble, “You bumped into me!”

As Dan drove along, Penny and I counted off the towns, down whose Main Streets we went because there were no bypasses then: Meredith, “The Latchkey to the White Mountains”; Center Harbor with its fascinating fountain dwelt in by a naked boy clutching a goose. Then came the turnoff onto the Moultonborough Neck Road. Nowadays it’s busy with a big hardware store and other businesses, but all I remember there then was maybe a gas station on the right and, definitely, an ice-cream stand on the left where, if Ernie was feeling very indulgent as we started home, we stopped for ice-cream cones. (Once, as I’ve mentioned in “Children of the Great Depression,” for some reason we hadn’t had supper, so Dan and Ernie bought a chicken basket for us all to split, an unheard-of extravagance.) We’d turn right onto the Moultonborough Neck Road, and the trip would really seem to drag as we continued the six miles down the neck.

On hot summer weekdays we sometimes made the trip after Dan finished his day’s work in the time-study department of Scott & Williams, to have a swim and the picnic supper Ernie had packed—deviled-ham sandwiches, olive-butter sandwiches. But usually we went on weekends and camped out.

On hot summer weekdays we sometimes made the trip after Dan finished his day’s work in the time-study department of Scott & Williams, to have a swim and the picnic supper Ernie had packed—deviled-ham sandwiches, olive-butter sandwiches. But usually we went on weekends and camped out.

Dan pitched a big tent that he had designed and Ernie had sewn. In it we spent the nights. Penny and I can still smell the inside of that tent, the pine boughs Dan cut for us to sleep on, the wool smell of our itchy blankets, the tent’s canvas smell mingled with the faint reek of whatever stuff Dan had used to waterproof it. Penny became the subject of a family tale about how she was so little that one night in her sleep she rolled out under the edge of the tent, where Dan discovered her the next morning, still sound asleep.

Dan was the cook on these weekends, using his Coleman stove, and Penny and I remember the breakfast smell of bacon.

A big project was his building a wharf. It became a sort of porch to the tent in the woods, so in addition to swimming from it we sat there, and when friends and relatives visited, it was the gathering spot.

Our boat-building Uncle Lou made a rowboat for the Doan family. Uncle Lou’s talents were always doubted by Ernie, his sister, and to her satisfaction she was proved right in this instance: The rowboat leaked, though not enough to keep Penny and me from catching many sunfish from it. Dan had taught us to thread the worms on our hooks, a procedure both horrifying and mesmerizing. Penny was far more skilled at fishing than I was. I never could bring myself to detach a flopping sunfish from the hook, so Dan had to do this for me. Because sunfish were considered not worth eating, back into the lake they went.

Our boat-building Uncle Lou made a rowboat for the Doan family. Uncle Lou’s talents were always doubted by Ernie, his sister, and to her satisfaction she was proved right in this instance: The rowboat leaked, though not enough to keep Penny and me from catching many sunfish from it. Dan had taught us to thread the worms on our hooks, a procedure both horrifying and mesmerizing. Penny was far more skilled at fishing than I was. I never could bring myself to detach a flopping sunfish from the hook, so Dan had to do this for me. Because sunfish were considered not worth eating, back into the lake they went.

It wasn’t simply summer days. We went to the Lot in the spring as soon as the snow melted enough and as late into the fall as snow allowed. Penny remembers one winter day when she and Dan drove to the bridge, put on snowshoes, and snowshoed along the lake to the Lot, Penny worrying about the thickness of the ice.

But summer days predominate in our memories. Penny and I played our various games in the woods, sometimes with friends who came with us. Penny remembers how she and Mary C. decided that a big rock would be a hotel and began clearing smaller stones out of the lake in front of it to make a sandy beach. They asked me what the hotel should be called, and I named it “Pine Overhead Hotel.” We also had times of solitude. Penny was in her element, exploring, learning, relishing flora and fauna. As usual my nose was in a book, but I tried to think deep thoughts about appreciating nature.

One thought was that this enchanting piece of land should have a better name than what we called it, the Lot. After much pondering I came up with “Chipmunk Hollow.” But Dan, referring to our joyous yells of release when we leapt out of the car upon arrival, as well as our shrieks when we jumped off the wharf, remarked that “Whoop and Holler” would be more accurate. So I made a sign illustrated with a drawing of Penny and me with our mouths open, and Dan nailed it up on a tree. Yet of course we never did call the place anything but the Lot.

And we all loved it.

Then somebody from Massachusetts bought the lot beside us and began building a snazzy camp (as I’ve explained far too often elsewhere, “camp” was the term for cottages back then). We no longer had the woods and lake to ourselves. Our idyll was spoiled.

And the trip was long, and the old Mercury was getting older, less trustworthy for these constant trips. Finding themselves in a situation that reminds me somehow of “The Gift of the Magi,” Dan and Ernie decided that they had to sell the Lot to buy a new car. So eventually we had a new 1951 green Ford. But we didn’t have the Lot to drive to.

In Sandwich, I live much closer to Moultonborough Neck, and at least once a week I drive past the Moultonborough Neck Road. Back during our courtship (!), Don and I drove down it to the bridge, which is part of Don’s memories too. When he was at Camp Belknap in Tuftonboro at age five or six, the counselors took a boatload of little boys over to Moultonborough Neck, where they fished under the bridge. (Sunfish again.) Although we’ve lived so near for thirty-five years, we’ve only gone back down the road a couple of times. The place is packed with cottages now and resembles nothing I remember from childhood. But needless to say, though say it I will, the real place exists in memories.

Copyright 2011 by Ruth Doan MacDougall; all rights reserved

MOTHER GOOSE

June 24, 2011

On the first of May this year, Don looked out a kitchen window and noticed that one of the two Canada geese who’d showed up in our backyard beaver pond had climbed up on the abandoned beaver lodge. This was not unusual; in years past we’ve seen Canada geese occasionally sitting there, apparently liking the vantage point, as they do the top of the rock that sticks up out of the pond, a rock we could walk past before the beaver moved in; now, we’d have to swim.

(To sort out the rocks in the pond, we call this one Rock Ruhamah. Ruhamah was the name of an ancestor, and my mother had been tempted to name me that but instead named me after a more recent relative, her mother. When Don and I were living in Farmington, NH, and I first explored the woods around our house, I “discovered” a huge boulder [as my father remarked, “How could you miss it?”] and gave it the almost-name of the discoverer, me. When we moved here to Sandwich, we named the tallest rock in the backyard after that Rock Ruhamah in the woods. I digress. As usual.)

But this goose wasn’t just sitting on the lodge. It poked with its bill around its—er—bottom, fussing with whatever it was sitting on. Don got the binoculars and called to me. We watched the fussing. Was the goose a female, making a nest?

We’ve never seen Canada geese stay here to nest. On their return north in the spring, they stop at the pond to refuel and after a few days they flap onward.

In the following days we kept an eye on the lodge, and on May third we again saw her sitting on what must be a nest. She continued to sit the next day, in the rain.

The next day was clear, and at five o’clock that morning I saw her still sitting there, her reflection upside-down in the limpid brown-green water. Three hours later the male appeared, swimming from the west, the direction of the biggest part of the pond, which we can’t see from the backyard because of woods. We were surprised that he evidently was living somewhere over there, not nearer. The female got a breakfast break that lasted about ten minutes, swimming with the male to the head of the little inlet we call Beaver Bay. As she fed along the bank, he swam nearby, apparently guarding. Then together they sat on the rock we call the Preening Rock, where ducks as well as geese like to sit and do their grooming and preening. Then she swam back to the lodge and clambered up to the nest.

By now, we were looking for her out the window whenever we were in the kitchen. When we were on the back porch or in the yard she was a constant presence on the lodge. Nature camouflaged her, so we often had to grab the binoculars to make sure that, like the flag, she was still there. Sitting, sitting, sometimes her black neck high, sometimes tucked down.

And by now, of course, we had named her Mother Goose.

We have a little dinghy for exploring the pond. It too has a name: Lily Pad. We gazed at it, drawn up on the lawn at the end of Beaver Bay, and longed to row out to the lodge for a closer look, but we didn’t want to scare her, though we suspected she’d be more apt to scare us with a flying attack, as might her mate. We remembered how in England we’d sort of overcome our fear of the swans who awaited us when we took our fish-and-chips down to the river for a supper picnic. I wrote about this in A Lovely Time Was Had by All:

“As we walked down the green riverbank to the green river, one of the swans snarled at us. Jacob opened a bundle, selected a large vinegary chip, and tossed it to the swan. The chip buckled in midair; the two halves plopped into the water.

“A civilized distance away from the lock keeper’s cottage, near the towpath we spread our jackets on the wet grass littered with ice-cream sticks and soggy feathers, and while more swans cruised up we sat and threw them their ration of the chips and ate our pieces of plaice. In the drained sky the stars barely glimmered. I hoped a boat would come by and go through the lock.

“The first swan to realize the food was gone swam away, climbed up on a sunken log near the bridge, and dug his bill into his feathers like a dog after a flea. Until this summer I hadn’t known how big and ill-tempered such beautiful birds could be or how they managed the problem of their necks when they slept by curling the lengthiness back along their bodies. Sometimes we took night strolls here just to see the swans sleeping, floating white and headless on the inky river.”

Don and I did some research about Canada geese and learned that they mate for life and that our Mother Goose would be sitting on her nest about twenty-eight days until the goslings hatched.

One afternoon, Don saw Father Goose swimming in midpond. Mother Goose flung herself off the nest and flew honking to join him, and all Don could think of, he told me later, was those reunions at airports with wives rushing toward their soldier husbands home from the war. The geese then proceeded to feed and preen.

On the afternoon of Mother’s Day, we spotted the pair swimming back to Beaver Bay from wherever else they’d been in the pond. She stepped briefly onto land, while he guarded. Then she returned to her duties. We thought of all the mothers being taken out to dinner.

A few days later we saw Mother and Father returning from the western end of the pond, honking and splashing. He climbed up on the lodge near the nest and stood tall, king of the mountain, while she fed at the edge of the lodge. Then she climbed up, laboriously, taking her time. We were reminded of my father’s descriptions of the difficulty of walking on beaver dams to fish from them. After she sat down on the nest and poked around carefully, he went down into the water, swam a bit, lingered, swam off.

Come evenings at that time of year, the spring peepers are LOUD, and we would picture her sitting in the darkness surrounded by this lovely racket, the tiny frogs keeping her company.

May fifteenth was cold and very rainy. Sheets of rain, gusts of wind, the pond swelling and shimmering. She sat. In the afternoon we saw Father Goose staying nearby in the water while she remained on the nest. We didn’t see her leave it that day and assumed that she couldn’t leave because doing so would expose the eggs to the downpour. The rain continued, cold day after cold day. Father Goose patrolled a lot or sat nearby on the Preening Rock. And she kept on sitting. We feared she would starve.

Some sun finally wavered out on the afternoon of May twentieth. Mother Goose left the nest and went off with Father, then returned and climbed back onto the nest. Later, Don saw them both swimming and was surprised that she was taking another break so soon. On the Preening Rock their preening was the most thorough he’d ever seen. She returned to the nest, then immediately jumped back into the pond. She followed Father Goose swimming away.

We never saw them again.

We can only figure that even her determined incubation couldn’t save the eggs from the cold wet weather. Her presence remains in phantom form, and we keep looking over there at the beaver lodge.

© 2011 by Ruth Doan MacDougall; all rights reserved

COLONIAL THEATER

March 1, 2011

“Remember,” asked Penny, my sister, during one of our weekly phone calls recently, “the walks home from the movies in the winter when the afternoons were dark?”

“Terrifying!” I said, shuddering.

This had been in the late 1940s into the early 1950s, when we were living on Academy Street in Laconia, New Hampshire. (Later, we moved to Gilford Avenue.) Back then, the news wasn’t full of children abducted, molested, murdered. We were not like today’s children who are, as Ruth Rendell put it in one of her mysteries, under a form of house arrest. We roamed all over our neighborhoods, playing without supervision, and when Penny and I walked to the movies we walked on our own nearly two miles.

This had been in the late 1940s into the early 1950s, when we were living on Academy Street in Laconia, New Hampshire. (Later, we moved to Gilford Avenue.) Back then, the news wasn’t full of children abducted, molested, murdered. We were not like today’s children who are, as Ruth Rendell put it in one of her mysteries, under a form of house arrest. We roamed all over our neighborhoods, playing without supervision, and when Penny and I walked to the movies we walked on our own nearly two miles.

After leaving our house, we usually stopped partway along Academy Street at the house of friends, Mary, who was near Penny’s age, and Ruthie (yes, yet another Ruth), who was two years older, my age. The age gap was vast, so Ruthie and I went on together, ignoring Penny and Mary who ran ahead or tagged behind. Our route led past the brick Academy Street School and the Belknap County courthouse, to Main Street, where we cut across a vacant lot over which a Cott Beverages billboard loomed. We continued on past the downtown stores such as LaFlamme’s Bakery (best chocolate doughnuts in the world), Oscar Lougee’s and Rosen’s and O’Shea’s (clothes, of more interest to us in later years), the nut shop (we never could afford cashews, but you could get a lot of Spanish peanuts for a nickel), the Western Auto hardware store (the upstairs at Christmastime a Santa’s workshop of toys), the Newberry and Woolworth five-and-dime stores (where we spent most of the part of our twenty-five-cents weekly allowance that wasn’t spent at the movies or on Spanish peanuts), and finally reached our destination.

Laconia had two theaters then. It was necessary to queue up a couple of flights of stairs to the Gardens Theater, a firetrap that specialized in B-movies, Westerns and Abbott & Costello and such, and thus appealed more to younger kids and males of all ages—I remember that once our father went with Penny and me to see a Hopalong Cassidy; we were young enough not to be mortified by his presence, but we did find his desire to see Hopalong awfully funny, as did our mother, who stayed home in blissful solitude. We kids sat through some unlikely stuff there, including movies that looked dated even to us. When I grew up and happened to read The G-String Murders, supposedly by Gypsy Rose Lee but perhaps ghostwritten by Craig Rice, I recognized in amazement that I’d seen a movie version of it at the Gardens! This was Lady of Burlesque starring Barbara Stanwyck. I’ve just checked the date on Google, and it came out in 1943. I certainly didn’t see it at age four, so once again the Gardens had bought something cheap.

The “nice” theater, which showed the main Hollywood offerings, was the Colonial Theater.

In addition to describing it in The Cheerleader, I wrote about it in my first novel, The Lilting House:

In its heyday this theater must have been very grand; its seats were cushioned, unlike the other theater’s, and there were boxes to the sides of the stage with gold railings and tassels; nobody sat in them now. There was an orchestra pit where no orchestra played, and above the proscenium arch was a painting of ladies almost naked, their drapery blowing, and cherubs, all soft blue and pink and gold. If you looked way up at the faraway ceiling, you saw an enormous chandelier.

Decades later I learned how we happened to have such a magnificent theater in Laconia. Benjamin Piscopo, born in 1864, was an Italian stonecutter who had made his fortune when he came to Boston and got into real estate there. He then moved to Laconia circa 1911 and continued his real-estate ventures. In 1913 he began the Colonial Theater project. According to an article in a 2010 issue of The Weirs Times, “he spared nothing . . . using master woodworkers, masons, and painters, many of whom had learned their craft in Italy, to create an Italian style theater which had 1,400 seats and was the site of vaudeville acts and motion pictures.” In 1915 The Laconia Democratreported that the Colonial was “one of the handsomest playhouses to be found in New England.”

The first time I went to the Colonial, it was to see a play made from The Secret Garden. I think I was still in kindergarten then; I can only remember a feeling of bewildered excitement and on the stage a wall with pastel flowers. The next time I remember being there was when my father took me to see The Red Shoes, the 1948 movie inspired by the Hans Christian Andersen story, with Moira Shearer as the doomed ballerina. I would have turned nine that year. I suppose I must have read the story or had it read to me and hadn’t been particularly bothered by its gruesome aspects, so my parents thought it would be suitable. They deemed Penny too young, so my mother stayed home with her. But the movie horrified me. The ending had red blood as well as red shoes! And I had nightmares.

Despite this, however, I became part of the groups of kids spending their Saturday afternoons at the movies, watching the previews followed sometimes by a newsreel, sometimes a cartoon, and then the double features.

Sandy is a friend from a younger generation whose love of old movies, especially musicals, has made me realize how lucky I was to have seen them when they were brand-new. In the Colonial I sat enthralled through musicals from Show Boat to Singin’ in the Rain. As I’ve written elsewhere, An American in Paris is still my favorite movie ever. There were lesser works, of course, such as On Moonlight Bay and By the Light of the Silvery Moon, and maybe we got rather sick of Doris Day and Gordon MacRae. But we gobbled the whole gamut along with our popcorn. I would leave the theater humming, trying desperately to remember lyrics, such as the clever ones sung by Fred Astaire and Jane Powell in Royal Wedding’s “How Could You Believe Me When I Said I Loved You When You Know I’ve Been a Liar All My Life?”: “—You’re really naïve to ever believe a full of baloney phoney like me!” (The name “Alan Jay Lerner” in the screen credits meant nothing to me then, but I loved that song.)

Don, my husband, whom I didn’t know in this childhood part of our lives, has his own memories of the Colonial. There was an emergency exit door that could be opened from the inside onto a side street. The boys would chip in to pay for one boy’s ticket, and, once inside, this kid would open the door for the boys waiting outdoors to slip in one at a time, on the alert for an usherette or the extremely forbidding manager.

Usually the balcony was closed during matinees, probably because kids up there would naturally start throwing popcorn on those below, but on rare occasions the downstairs was so packed that the manager had to open it—and then ensued a thundering stampede, mainly boys. Don recalls that it was kind of spooky to be up in the balcony, which wasn’t well lit.

During “mushy” love scenes, Don would head for the lobby and the lengthy candy counter. Nowadays, when I sense him beginning to squirm while we watch a DVD, I ask him, “Are you about to go buy some Necco wafers?”

In addition to the musicals and comedies and romantic movies at the Colonial, there were scary movies. I particularly remember one in which a lion was terrorizing a village; I ducked down behind the seat in front of me and stayed there, peeping fearfully through the space between it and the next seat. I didn’t go to see The Thing—maybe I had a cold and my mother kept me home—but Penny did and she has not recovered to this day.

Which brings me back to our recent conversation. Penny and I recalled that sometimes we walked home together from Ruthie and Mary’s house if we’d met up there after the movies, and that gave us courage. But in our memories we most often walked home alone from Ruthie and Mary’s, along the dark neighborhood street no longer familiar, lined with trees behind which terror lurked. Sometimes we broke into a run, but that was more dangerous because then it would chase us. Usually we walked, hearts pounding. Though what we feared wasn’t today’s very real terrors, our fears certainly felt starkly real to us. Behind that tree, that shrubbery, that telephone pole, there might be monsters—lions—The Thing!

Years later in the 1960s when Laconia ill-advisedly underwent an “urban renewal” that razed half of our beloved downtown, we rejoiced that the Colonial was in the section that was spared. But in 1983, to our dismay the Colonial was split up into a multiplex of five theaters. At least, however, the interior wasn’t destroyed during this; it could be restored. Now the Colonial is closed and for sale. The city of Laconia has an option to buy it, but these things are complicated and a “feasibility study” continues. Those of us with memories of music, romance, and terror do hope that our Colonial Theater can be saved.

© 2011 by Ruth Doan MacDougall; all rights reserved.

AEONS OF IRONING

January 6 2010

A Sequel to "Loads of Laundry

After Winifred Motherwell read my “Loads of Laundry” piece in “Ruth’s Neighborhood” last year, she pointed out that an additional piece needed to be written about the “more or less permanent chore of ironing.”

Then she told me an ironing tale that made me gasp in admiration while my blood ran cold. When she and her husband were both teaching, she wrote, and their two daughters were in kindergarten and preschool, “my Sundays were spent ironing six dress shirts and eighteen dresses, all cotton, all needing to be dampened.” Eighteen dresses!

My mind went back to the Keene Teachers’ College married students’ barracks, where on Sundays in our apartment I first tackled this part of domestic bliss, ironing the week’s worth of clothes for Don and me, his shirts and khakis, my blouses and cotton dresses and skirts. To keep from going mad, I listened to LP record albums and even found a radio station that played old programs I’d listened to in my childhood, “The Lone Ranger” and such.

Winifred wrote, “By cold weather I could switch to sweaters and skirts but there were still the shirts and all those smocked, puffed sleeve dresses beloved by grandparents. I actually rather enjoy ironing now that I only have to do it every two months or so but back then my life was chaotic enough without having to devote a whole day to the ironing board. I’d play Clancy Brothers records as background because I’d speed up with the jigs.”

My mother grew up in Lexington, Massachusetts, so of course she was a Red Sox fan, but she had never really paid attention to the games until she found herself married, on a farm in New Hampshire, listening to the radio while doing the ironing. Baseball games were her favorite distraction from the chore. She became a real authority on them and began listening even when she didn’t have ironing to do. A predominant sound of summer in my memory and my sister’s is a radio sports-announcer’s voice and the whoop of the crowds.

In “Loads of Laundry” I recounted how in junior high school my sister and I would spend Sundays starching and ironing our outfits for the week ahead. Winifred reminded me of an extra challenge, “those popular full-skirted shirt dresses of the 50s and early 60s. I think the skirts were two yards around at the hem and they were so long the skirts had to be ironed in two circuits, one for the gathers at the waist and then back around for the rest of it.”

This in turn reminded me of “circle skirts,” which I seem to recall I even made in home-ec class as well as under the direction of my grandmother; you cut a great big circle out of the cloth, with the waist in the middle. When I mentioned them to Winifred, she wrote, “Circle skirts, and they were circles, were fairly easy to iron, except for keeping the freshly ironed part off the floor. They probably could even be done on a mangle, but the full skirts worn over crinolines had tiny gathers that needed the iron’s point. There was a ghastly concoction called Permastarch that was applied somehow, and then they had to be dampened to a perfect and nearly unobtainable state between too wet and too dry, like practically everything else.”

Winifred had told me earlier that her mother and mother-in-law had mangles; “I could use them but it never seemed worth the effort and they took up an awful lot of room.” In “Loads of Laundry” I’d written how Don’s mother had ironed his khakis on her mangle. My mother used pant stretchers for my father’s. Winifred said, “Even with a mangle and after having been wrestled on and off pants stretchers those khakis of the 50s were torture to iron. They were made of either canvas or concrete, it seemed, and were totally unwieldy.”

Tom, her husband, known to us as the Real Tom to differentiate him from Snowy’s Tom, “usually wore oxford cloth buttondowns but still had some broadcloth dress shirts, like the ones my father wore, when we were first married. They had to be starched at least occasionally, and dampened, of course, and scorching the last front side was inevitable. Table linens from holiday dinners always scorched easily too. And my school gym tunics defied description.”

Winifred added, “As you can tell, I’ve spent an awful lot of time ironing. But I’ve never had a good place to do it, it’s always had to be the kitchen or dining room. When the girls were little the ironing board was such a permanent feature in the dining area I started referring to it as the room divider.”

I learned to iron in the bathroom. My mother kept the ironing board set up in the downstairs bathroom off the kitchen, where the washing machine also resided (most people didn’t have dryers then) so there was some logic to the location. I later realized how convenient it was, for never afterward did I live anyplace where there was room to leave the ironing board open, so I’ve always draggedit out of broom closets or, in this present house that doesn’t have such a closet (and only two regular closets, one of which Don built), out of a space beside the refrigerator.

My mother’s first steam iron was temperamental, apt to spit water. This didn’t cause too much trouble with cotton, but with delicate fabrics it could cause stains. I can still hear my mother’s cry of dismay when the iron erupted while she was pressing the skirt of the outfit I was to wear that evening to the seventh-grade reception. Because of the trickiness of its fabric, she was doing the ironing, not me. I’d been much influenced by Leslie Caron’s clothes in An American in Paris, which I’d seen and loved that year (and ever after), so instead of a party dress I had chosen a deep pink skirt in some sort of taffeta and a sheer white blouse with long puffy sleeves and a black velvet vest that my grandmother made. Now my mother was crying over the line of water stains at the bottom of the skirt, perpendicular to the hem. She wasn’t a person who usually lost her head over such disasters, but I was the president of the seventh grade and had to give a little welcoming speech at the beginning of the reception in the high-school gym, so even though I was just a kid my outfit would really be noticed; I couldn’t hide at the back of the gym. She wept and exclaimed, and for the first time that I can remember I remained calm during a crisis, maybe because all my worries were concentrated on giving that damn speech. I suggested a solution: sewing a seam to hide the stains and decorating the seam with black velvet bows, as if it was meant. I had black velvet ribbon on hand because I was going to wear a piece around my neck as a choker. (I really hadplanned this outfit, right down to the black ballet flats in which I could dance with Gene Kelly to “Our Love Is Here to Stay”!) The solution worked. My boyfriend Roger Thibodeau, known as Tibby, and I were driven to the school by my father, with my mother, who were chaperones, and I got through the speech, and afterward while Tibby and I danced I thought as much about the treachery of steam irons as I did about romance.

Steam irons did improve. Another great leap forward were no-iron clothes, even the polyester ones. Eventually there were some afternoon programs besides soap operas to watch while doing the ironing and then, hooray, came audiobooks! Nowadays I do a lot less ironing than in days of yore and I actually look forward to it as a time when I can listen to a book on my Walkman or CD player.

Days of yore. From my grandmother’s house I still have a couple of the old iron flatirons that women had to heat on stoves. One I use as a doorstop, and the other is a bookend on my desk. My gaze falls upon the latter more often than the former, but I’m usually not really seeing either, and then suddenly at my desk I realize with a jolt what the bookend is, its history, and I see women through the ages working at what Winifred so aptly called this more or less permanent chore.

© 2010 by Ruth Doan MacDougall

All rights reserved

OUR CANTERBURY TALE

September 19, 2010

This entry was expanded into an essay, with photographs, in the Literary Pastimes Anthology; HERE.

i LOVE IT HERE

August 12, 2009

Ruth is asked by a New Hampshire travel magazine to submit photos of her favorite spot in New Hampshire. Would you like to guess where her favorite spot is? I LOVE IT

When the New Hampshire Division of Travel and Tourism Development invited me to become one of the New Hampshire “celebrities” participating in its “I Love It Here” campaign I was asked to have my picture taken holding an “I Love It Here” sign and to send it in with a list of some of my favorite New Hampshire locations.

Readers of my “Neighborhood” pieces won’t be surprised that my favorite place is our backyard. Don snapped a photo of me here, in front of the beaver pond and the beaver lodge that we had watched with concern throughout the winter. Over the years, the beavers have stripped the land of the nearest hardwoods (including those in our backyard we didn’t guard with wire fences), and last fall we didn’t see them storing any branches near the lodge for winter food, so we feared they would starve to death.

This spring we watched and waited, fearing the lodge was a mausoleum. And then one April evening, as I was looking out the sink window I thought that the silhouette of the lodge had an extra bump. Wishful thinking, I told myself, but I called Don and we went out to the porch to peer through the twilight. And the bump moved, became a beaver silhouette.

We cried, “They made it!”

Next, on the morning of April 21, we were at the windows of my upstairs garret office, Don preparing to take them apart to replace rot. Below, the expanse of brown pond and beige grasses was gold in the sunlight. Suddenly we saw a small beaver swimming so fast that we wondered if it was a beaver. They usually proceed in a businesslike manner, steaming along purposefully. This one was racing. Then we saw another, the same size. The two began splashing, tussling; the sheer exuberance was obvious. These two young beavers were greeting springtime. Born the previous spring, they had been cooped up all winter in the lodge with their parents, and today they were venturing forth for the first time. The tussling ended and they zoomed off in separate directions amongst the little islands and inlets, vibrant with curiousity and the joy of freedom. One returned to swim at full speed back and forth below us, rejoicing—whee!

And thus the life of the pond began again. On June 6 we spotted six ducklings in an obedient little line behind their mother. A few days later, the group went past with the ducklings in front, mother behind, “as if,” Don remarked, “she’s pushing a log.”

June means turtles to us, too, and one duly appeared in the backyard. There’s a rock that sticks up out of the pond, a rock we used to walk around, back when the pond was just a brook. Turtles love to sun on it. And ducks make a stop there every afternoon about four o’clock, to clamber out of the water and groom. For the first time I saw a heron on the rock instead of on the shore. It stood very still, showing off its curves.

As spring became summer, we saw herons more often, flying over the pond, sitting in trees, standing and grooming for an hour, or pretending to be invisible while waiting for a fish or frog. The patience of herons! I’m always reminded of a description in my father’s novel Amos Jackman, of Amos fishing in the rain: “He lost track of the time he waited, for he wasn’t thinking or worrying about the rain, just fishing with the patience of a heron hunched on the shore.”

One August day we saw a young heron walking across our lawn between the garden and the pond. We’d never seen a heron inland, so to speak. This happened again a few days later, when the same (we assume) young heron appeared even closer to the house, between the ell and the shed. He headed toward the woods, not the pond. Was he lost? Did he lack some built-in pond-tracking device? Or was he, like the young beavers in springtime, just free and exploring?

We’ve seen a bear a couple of times in the backyard this summer, but both times the bird feeders weren’t out, so they weren’t raided. On a trip to a nearby town we saw a moose in the woods along the road, but we haven’t yet seen one in our backyard this year. But I did discover moose tracks marching through our squash-and-sunflowers patch, miraculously missing each plant.

Now in mid-August we’re beginning to worry again about how the beavers will get through the winter. We’ve read how they can adapt their diet, and this summer we’ve seen them eating the lush weeds on the shore and dragging jawfuls to the lodge. As we did last year, we’ve seen them grazing on the lawn beside the pond, keeping it cropped so close we don’t really have to mow that area.

I’ve mentioned in an earlier piece my fondness for Margery Sharp’s novels, in particular The Nutmeg Tree and Cluny Brown. This summer I found myself looking up a favorite quote in the latter, as Cluny, a city girl, discovers the countryside:

“At every step almost there was something to look at, something to come back to; and with an unusual flight of her town-bred imagination Cluny suddenly thought that if she came back this time next year, everything would be more interesting still, because she would remember this walk, and all the changes that had come between. She had a glimmering, in fact, of the true pleasure of country life, which is not to be enjoyed merely at a summer weekend; the word continuity was not in her vocabulary, but she groped for it; and in her shaken-up frame of mind these new ideas struck home with extraordinary force. Because if there was space, there was also depth: you could unroll all the countries of the world, thin as maps, or dig down among the roots of your own patch.”

© 2009 by Ruth Doan MacDougall

All rights reserved

CHILDREN OF THE GREAT DEPRESSION

May 14 2009

The economic realities of the Great Depression continue to shape the attitudes and habits of those who lived through it—or those whose parents lived through it.

The other day in the kitchen, Don held up an old chambray shirt and asked, “Is it time to get rid of the collar?”

The collar was very frayed on the inside.

I said, “I could turn it.”

We laughed, because I hate to sew, but we both knew that I could save the collar if I had to. In fact, during a phone chat with my sister some days before, Penny and I had discussed the thrift tips that are being given so often on TV and in newspapers and magazines in these trying times, and I’d remarked, “I haven’t seen one yet telling how to turn a collar,” and she said, “Or darn a sock.” Amongst the many useful things she and I learned from our mother and grandmother was how to do such things. During early married years we’d thus extended the lives of the shirts and socks of our schoolteacher husbands and also our own clothes, in addition to general mending.

As Don stood there contemplating the chambray shirt, I realized that he hadn’t asked if it was time to get rid of the shirt, just the collar. This is the system in my post-collar-turning years; we cut the worn-out collars off the shirts and keep on using them. Sort of mandarin style. We were both, I thought, still influenced by our parents and the Great Depression.

Don took a pair of scissors out of a drawer and carefully cut off the collar.

And I saw hanging on the door behind him the roller towel that had belonged to my parents. It’s not the most hygienic thing in the world, but I’d kept it out of nostalgia—and that sense of frugality that we cannot rid ourselves of. Why dry your hands on expensive paper towels instead of on a roller towel that can be washed and reused for years? The roller towel seemed to sum it all up. (I hasten to add that I do also have a roll of paper towels on the kitchen wall. The “select-a-size” variety, of course. But if I’ve used a sheet only to, say, dry off a washed tomato, I hang it on the clothes rack to dry and use again. This is so embarrassing to admit! Blame it on the Great Depression.)

Don’s parents and mine were, with variations, in their teens, twenties, and thirties during the Depression, and like all their generation they were influenced by it the rest of their lives.

When my father graduated from Dartmouth in 1936, he and my mother, who’d grown up in the Boston suburb of Lexington and never quite got over the shock of spending the rest of her life in the wilds of New Hampshire, took up chicken farming in Orford, near the Doan family home. They shared this back-to-the-land Depression adventure with my uncle and aunt; that is, my father’s sister and my mother’s brother, who had met and married a few years earlier and were the reason my parents had met. I’ll supply names to try to keep this complicated relationship clear: My parents were Dan and Ernie (Ernestine); my uncle was Lou and my aunt was Ib (Isabel). They lived together in somewhat separate quarters in an old farmhouse on Dame Hill. Dan later relished referring to this as the first New Hampshire commune. They managed to survive by living off the land (and sometimes with cash help from my grandfather, Ernie and Lou’s father). Ernie and Ib canned the garden’s vegetables, but according to Ernie this sweltering chore on a woodstove in summer heat waves was even more arduous because of Ib’s competitiveness; the canning became a contest to see who could do the most. Ernie said that Ib canned in pints because the total sounded like more than Ernie’s quarts. Dan found the rivalry a lot funnier than Ernie did.

Of course Ernie soon had enough of such togetherness. She and Dan moved their chickens to a farm in Belmont, NH, and during the last years of the Depression they continued living off the land, getting by. Of the many stories they told about that time, one of Ernie’s favorites was about surplus, the luxury of having more than you need. She tried to use up all the extra eggs, making sponge cakes with the yolks and angel cakes with the whites; she tried to use up all the milk from Nancy Belle, their cow. But sometimes she just couldn’t, so she allowed herself a new rule: “Use what you want and throw the rest to hell!”

Then came the War, and when I was three and Penny a baby, we moved to an apartment in Laconia and Dan did war work at the local factory. The Depression might have been over, but it remained in Dan and Ernie’s souls.

So, like other parents from that generation, they passed their anxieties, skepticism, roller towels, and soap-savers down to our generation. Though we laughed at their fears and quirks and obsessions, the Depression definitely was within us too. (For the edification of younger readers: What we called a soap-saver was a small wire basket with a handle; in the basket, scraps of soap were accumulated, and you whisked the basket through the water in the sink to make suds for washing dishes. I think soap-savers still might be available at the Vermont Country Store.)

There were many of these quirks, idiosyncrasies, and ingenuities. The mother of a friend always tore paper napkins in half, figuring a half was enough for one person. The furnace was turned way down or off at night, so winter mornings were very cold. It was drummed into us that we must switch off a light when we stopped using it, and woe betide us if we forgot. Hot water was precious, baths monitored. Men saved old nails, screws, nuts, and bolts in old jars. People saved everything, in case it could be used again, from the aforementioned soap scraps to elastic bands, threadbare towels, wrapping paper, everything. Pimento-cheese spread came in cute little jars, and it seemed like everybody used the empties for juice glasses. But “recycling” wasn’t in our vocabulary.

Leftovers became new creations. Ernie ground up the remains of a roast and mixed it with leftover gravy to serve over mashed potatoes, a dish that was as much fun as the Sunday dinner. If there was stale leftover cake (hard to imagine, but sometimes there was), she made a custard and crumbled the cake in; delicious.

Although you could buy some things “on time,” people mostly paid cash. Everyone in our neighborhood had acquired refrigerators one way or another except for the parents of one of my friends, who kept using an icebox because they hadn’t yet saved up enough money for a fridge. Ice deliveries to homes had stopped by then. I remember going to the icehouse with my friend and her mother to pick up some ice. The icehouse’s sales were mainly to businesses at that stage, and the man in charge must have made some derogatory comment to her mother about still using an icebox. I didn’t hear it, but I saw her mother weep.

Rarely did the Depression mentality permit dining out. An ice-cream cone was a great treat, and Don and I still talk about the Double Decker dairy bar where sometimes our parents would splurge, buying the kids the double-decker of two scoops. I point out to Don the hallowed spot where there used to be the drive-in restaurant that my folks once stopped at on a trip with Penny and me; because it was suppertime, instead of cones they bought a chicken basket for us all to share. I was so awed I almost lost my appetite. Almost.

In his Indian Stream Republic, Dan wrote, “Values a man learned in boyhood were his measure of commodities, property, and possessions all his life.” These Depression values certainly stuck with our parents, and the rising costs over the ensuing years seemed scandalous to them. We, their children, have our own measures we can’t escape. In my childhood, my weekly allowance was twenty-five cents. When the recent increase in the price of a first-class stamp was announced, I suddenly thought that forty-four cents was almost two weeks’ allowance, and I heard myself gasp.

-

© 2009 by Ruth Doan MacDougall; all rights reserved

LOADS OF LAUNDRY

January 23, 2009

Ruth reflects on the ways that she's done the family laundry through the years.

At this time of year, winter, I have to hang the laundry indoors to dry. Our indoor clothes yard is upstairs in the front part of my garret office, so I walk past it every day to get to my desk, and every day it makes me think ahead to the first time I’ll hang the laundry outdoors come spring.

And that first time each spring, pinning our clothes on the line that reaches from the side of the house to a tall pine at the edge of the beaver pond, I am suddenly twenty years old again, it’s the autumn of 1959, Don and I have just set up housekeeping in an apartment at the Keene Teachers’ College married students’ barracks, and I am blissfully hanging out our first load of laundry in the barracks’ clothes yard.

Those barracks found their way into a couple of my novels. I gave our apartment to Tom and Joanne in Snowy and, earlier, to Polly and Brad in The Cost of Living. I gave Polly our washing machine too.

The married students’ barracks at Avery were two long gray wooden shacks behind a cyclone fence, and Polly and Brad’s apartment was at the end of the first one, so it had more light. Their windows looked out at the clothes yard of sheets and diapers . . . Polly and Brad bought an old washing machine for fifteen dollars. It was the kind that was supposed to be bolted to the floor of a cellar, but since that was impossible here (we had no cellar underneath, just stray cats), Polly had to run and sit on it during its spin cycle so it wouldn’t start walking across the kitchen floor. There you might find her when you stopped by to visit, perched on her Bendix, studying.

That Bendix was the last washing machine we owned for many years. After we graduated, we lived in an apartment in Sharon, Massachusetts, and a rented house in Lisbon, New Hampshire, and I went to laundromats. I hated laundromats, from the questionable hygiene to the coin slots that jammed as if gleefully knowing that I was a klutz with machines.

After Lisbon, we moved to England for a couple of years. We crossed the Atlantic on the Queen Mary, and midway during the voyage we went into its laundromat with our laundry bag and encountered a time-warp shock. Instead of automatic washers, the ship had an array of old-fashioned machines just like my mother had used in the Laconia apartment of my childhood. My mother would haul that machine alongside the kitchen sink to hook to faucets for filling, and when the washing part of the chore was finished she hoisted the clothes out into the spin basket that my sister, Penny, and I were warned never to go near or we’d get our fingers cut off. All the mothers of our friends had these machines or the ones with wringers instead of spinners; we were told that the wringers were even more dangerous.

Our first year in Brandon, England, Don and I lived in one of the two apartments in Brandon Park’s old laundry cottage that I described in fictional form in A Lovely Time Was Had by All:

The cottage I’d rented was in Clopton Park. A fairy-tale forest cleaved by fire roads, this estate had become a plantation of conifers and you could see far into the ranks of trees because underbrush wasn’t permitted. Geese walked in the dooryard of the little stone storybook gatehouse. A gravel lane led to the manor house, which, along with the remodeled stables and laundry cottage, was rented by the U.S. Air Force Officers’ Club who in turn rented its rooms and the apartments in the outbuildings to Air Force people seeking off-base housing . . . Ivy climbed the old pink walls of the laundry cottage, picturesque and enchanting.

Out our kitchen door ran a clothesline across the little backyard, but I didn’t do any laundry in the laundry cottage, except hand washes, because it had no washing machine. However, several enterprising people supplied needs at Brandon Park, and I discovered that here in England (with Don getting an American salary) I could afford the luxury of sending laundry out:

. . . many products were brought right to our doors. There was the milkman who arrived every morning . . . Three times a week the breadwoman’s van came honking through the forest and all of us Clopton Park womenfolk and children gathered under the trees to wait until she parked it and opened the doors in back . . . The butcher’s car was a miniature station wagon, and his young helper carried to us in a big wicker basket the meat we had ordered. Kerosene was delivered once a week in a bus that combined a grocery store and a hardware store . . . And eventually, when I tired of going to the Base laundromat, the laundryman came to me. I kept thinking of my grandmother and how she would have been perfectly at home here.

My mother would’ve been, also. Although she did most of the laundry in that spinner washing machine, she did send my father’s white shirts out; that is, she and Penny and I walked down the street to Mrs. Flack’s house to deliver the shirts, and a day or so later we walked back and got them all starched and folded. In her busy kitchen Mrs. Flack made pies and doughnuts to sell, and she always gave Penny and me doughnut holes. (The memory inspired a character in A Woman Who Loved Lindbergh.) Somehow the shirts didn’t smell of cooking, so Mrs. Flack must have separated her various jobs. This didn’t happen when, during our time in England, we spent six weeks in a bed-and-breakfast in Oxford where the young woman who helped with the cleaning also took in laundry. She must have hung the wet clothes over her stove while doing a fry-up, for they smelled of sausages and chips. That ended the luxury of having laundry done during our stay in Oxford, and instead I hied myself to an Oxford laundromat, as did A Lovely Time’s narrator:

At Pembroke Street, Jacob gave me the laundry bag and entered the soot-blackened old house in which his tutorials were held, and I went on alone down the street to the laundromat. The rain began while I was reading there. As the sky darkened, the grimy laundromat seemed to grow brighter and cleaner, a white world safe from the storm. It could be anywhere at all, I thought, except for the kind of money you put in the machines . . .

And speaking of Mrs. Flack’s starched shirts, I’m reminded of how much starch we seemed to use back then. When my parents bought a house in 1951, they also bought an automatic washing machine. Modern living! But as Penny and I progressed into junior high and high school, we did lots of extra work on our clothes, starching our blouses, rolling them up in towels and stowing them in the refrigerator, every Sunday ironing five blouses each for the school week ahead. We stiffened our crinoline petticoats with gelatin or starch. Friend Molly Katz recalls that in New York she used a sugar solution on her crinolines and dried them on an open umbrella. Friend Gloria Pond says, “In Illinois we used starch or sugar, ironed them wide and stored them in a cone-shaped stack in the corner.”

After England, Don and I lived for a year in a studio apartment on Boston’s Beacon Street. It had a washer and dryer in a little room next to our apartment, very handy, but you had to time your laundry schedule around the schedules of the other people in the building. Then we moved to an apartment in Dover, New Hampshire, and I was back to going to a laundromat, usually on a Wednesday night to avoid the weekend rush.

In 1971 we at last bought our first house. It was a prefab log cabin (a fictional version of which I gave to Carolyn in Wife and Mother) in Farmington, New Hampshire. We bought our first new appliances. I loved the new washing machine and dryer almost as much as the twenty-five acres of woods around the place and the apple orchard and bog (these I gave to Bev and her parents in The Cheerleader, plunking down a fictional Cape and barn where our log cabin had been built on the site of the town poor farm).

When we moved here to Sandwich in 1976, the appliances came with us. During the ensuing years the washing machine has been replaced twice and the dryer once. Most of the time, though, when things go wrong with the washing machine or dryer, Don can fix them. I call him our Laundry Officer.

Don’s laundry career began in his childhood when he worked for his grandmother, who owned the Green Arrow Cabins in the Weirs. I gave his job to Polly in The Cost of Living:

Beyond the Grange Hall was Helen’s folks’ boarding-house Helen had grown up in, and as we drove on, we passed the house Polly’s grandparents had later moved to and the Blue Gate Cabins they had built. On the back porch of that house Polly and Sandra had worked washing sheets in the old wringer washing machine when they were still too small to reach the clotheslines to hang them up.

The sheets, when dry, were run through the Green Arrow’s mangle by his grandmother or mother. His mother had her own mangle, and during his high-school years she pressed his khakis in it as well as sheets and other linens, so his crisp-pressed pants were added to the charms that we girls noticed—and no doubt they helped him be voted Best Dressed in his yearbook, an honor that delighted his mother, who by implication was also honored along with her mangle.

During his two years in the Coast Guard, Don was the laundryman on his ship, the Escanaba. He chose the duty because he could be his own boss and make his own hours. I wasn’t exactly thrilled about this choice when I learned that the laundry was positioned in the bow beside the five-inch gun. He preferred to work at night, alone and independent, with the ship sleeping. The early-rising cooks were very friendly to him because he made a point of doing the extra laundry their job demanded, and when he got off duty each morning he’d go to the galley, where fresh-baked bread would be waiting and a cook would toss a steak on the stove for him. Over the two years, throughout storms off Newfoundland or moored calmly in Bermuda, he became skilled at laundering the variety of uniforms, but one time he was flummoxed: A group of officers’ wives and children had joined the ship for relocation and he was confronted by lingerie and baby clothes!

We had got married before he went into the Coast Guard. I was at Bennington and he was stationed in New Bedford, Massachusetts, when not at sea. (We'd meet in Lexington, Massachusetts, at my grandparents' house, which had a laundry chute that fascinated Penny and me in our childhood.) It was when he got out of the Coast Guard that we finally could start living together, in what I insisted on calling our love nest, in the married students’ barracks with the clothes yard I’ll be remembering this spring, outdoors at our clothesline, feeling twenty years old again.

© 2009 by Ruth Doan MacDougall; all rights reserved

SUMMER SUMMARY

September 12, 2008

Ruth describes some of the wildlife in her yard. . .

I said to Don, “We’re having a silent summer.”

I was exaggerating, yet something was definitely missing. We hadn’t had a silent spring; there was the usual amorous and territorial racket of birds and frogs, with occasional chipping from chipmunks. This chipping sound is part of our background noise and always makes us smile, especially when a front-yard chipmunk proclaims loudly the granite doorstep as his own sunning spot. But when summer progressed, the chipping ceased.

Last summer, too, our chipmunks disappeared, but we thought we knew what had happened, because it was obvious that some villainous creature had dug down into the front-yard chipmunk tunnels. We’d seen a weasel at the edge of the woods. We figured there had been a weasel massacre of chipmunks; the weasel or weasels had killed not only the front-yard family but also all the other chipmunks who never reappeared under the bird feeder or at the stone under the lilac bush where we always leave some seeds. Last year when friends of ours returned to their home after several days away, they discovered that a weasel had got in, wreaking havoc, and they deduced that he was the reason their chipmunks had also disappeared that summer.

This spring we waited, hoping to see some survivors or some newcomers who had discovered our bird feeder (which we call MacDougalls’ Golden Arches). And what joy when I spotted one at last! I rushed to tell Don, saying, “It’s the sole survivor, the Lone Ranger!” A few others appeared. But then they all vanished, and this year there weren’t any clues such as a dug-up tunnel or a weasel sighting.

We asked friends and they said that their chipmunks were scarce and also red squirrels and gray squirrels. But in Connecticut, friend Gloria Pond reported that “We have them, fat, stripy, shopping for the groceries of 2023 by our calculation.” So was it a New Hampshire phenomenon? Did the 155-plus inches of snow we got last winter have anything to do with it? Or all the rain? I asked Google, but I mainly was given directions to “Alvin and the Chipmunks.”

The beavers were scarce in our ponds this summer too. We have expected they would be moving on, because they’ve eaten themselves out of house and home here. Apparently, though, there’s enough food left to sustain a few, hooray! They might be living in a refurbished old lodge in the connecting pond, out of sight, to which they’ve moved occasionally over the years, or maybe they’ve built a new unseen lodge.

We missed the constant sight and sound of the beavers and relished what we got. We occasionally glimpsed one swimming past the overgrown abandoned lodge to check the main dam. When we read on the porch in the evening, once in a while we’d hear the slap of a tail on the water or the grated-carrot sound of munching on a branch. One day I looked out my upstairs office window and saw a beaver grazing on the strip of lawn between the pond and the garden. As I watched, out of the long grasses beside the pond came a baby beaver, and then another. They explored while she ate. We’ve seen beavers eating the succulent stuff at the edge of what we call Cress Cove, but this was the first time we’d ever seen a beaver eating grass. We saw her once again another day, and then no more. I hope she found a better source of food; it seems like grass would be impossible to store for winter. I think of her and the babies every time I mow that part of the lawn; in that strip, mowing wasn’t really necessary for some time because she had mowed it so thoroughly.

If we didn’t have as many chipmunks and beavers as usual, we did have bears.

The first bear to enter our yard was the biggest we’d ever seen, such a magnificent sight that we just stood rooted at the window, forgetting to run for the camera. (Well, since Don is recuperating from two knee replacements, I was the one who should have done the running. Together we kept forgetting throughout the summer.) Eventually we recovered our wits and made enough of a commotion so the bear tramped off. (The second story I wrote at age six was called “The Big Bear,” and I was proud of that “tramp” verb. This certainly was the bear of my imagination, so I might as well use the verb again.)

Next in June came Mama Bear and two cubs. She was a young mother, and the cubs were roly-poly. We stood enchanted on the porch, then at last shouted and clapped. All three ran up a tree beside the shed. But evidently cubs’ claws aren’t long enough to hang on for any length of time, because first one cub and then the other slid right back down. So Mama descended and herded them off into the woods.

One day when I was working in my office I heard Don yelling and rushed down to discover him out the porch door, on the back step, brandishing his cane, swearing at a bear who was trying to approach the bird feeder. It wasn’t that Big Bear but it looked formidable.

I said, “For God’s sake, don’t tackle him, let him have the feeder!”

Don continued yelling. I ran into the kitchen and fetched my parents’ large brass dinner bell with which my mother used to call my father down from the north forty for meals in their farming days. My wild clanging did make the bear back off toward the woods, but it wasn’t a full retreat. Nevertheless, Don headed out to grab the feeder off the pole, while I screamed at him to let me do it, I can move faster. Men! Stubborn! He did move fast enough to get back onto the porch with the feeder, and soon the bear gave up and returned to the woods.

The last bear adventure of this summer occurred in mid-July one evening after supper when I stepped blithely off the porch to take the compost bucket to the compost pile and met, coming toward me around the corner of the house, what appeared to be the same bear, the dinner-bell bear. Our reactions were identical. We both screeched to a halt and froze. For a stunned split-second we stared at each other. Then we both spun around and fled, me into the house, the bear thundering into the woods. Needless to say, the compost bucket did not get emptied that night.

We admitted defeat, as we usually do in midsummer, and stopped putting the bird feeder out, just as the experts tell us to.

-

Late in August, Don saw a chipmunk at the stone under the lilac. He reported this headline news to me, and we rejoiced. I’ve seen the chipmunk too now, but we haven’t yet heard him chipping. Nobody to warn off?

© 2008 by Ruth Doan MacDougall; all rights reserved.

Archive of Past Entries

2025

Red-Flannel Hash, Etc.

Family Recipes

Wider Eyelids

Donuts After Dartmouth

Castle in the Clouds

Dan Doan's Birthday

File Folders

Chocolate Lovers' Month

Piano Songs

Titles

Velveeta, etc.

Sandwich Board Greets 2025

Words

2024

PW 2025 Spring Preview

Christmas Vacation

Songs

D-H Trip

Gatsby & Icarus & Pudding

Yankee

Sides

E-BLAST and Sandwich Board

Sentimental Journey

Announcement & Creme Tea

Rosemary Schrager

British Picnic

Fall Food

September Sandwich Board

Soap and Friends

Autumn Anxiety

From Philosophy to Popsicles

Cheat Day Eats

Meredith NH

1920s Fashions

Old Home Week 2024

Honor System

Lost . . .Found . . .

Picnics

Aunt Pleasantine

Best of New Hampshire

Soup to Doughnuts

Tried and True Beauty. . .

A Shaving Horse, Etc.

Farewell, Weirs Drive-In

Backyard Sights

Thoreau and Dunkin’ Donuts

Cafeteria-and-Storybook Food

Lost and Found

Dandelions and Joy

Fiddleheads and Flowers

Pass the Poems, Please

Pete

Road Trip

Reviews and Remarks

Girl Scouts

Board, Not Boring

Postholing & Forest Bathing

Chocolate

PW's Spring Previews

From Pies to Frost

Island Garden

More Sandwich Board

Nancy

2023

Spotted Dick

Dashing Through the Cookies

Chocorua

Senior Christmas Dinner

The Sandwich Board

Nostalgia

Socks, Relaxation, and Cakes

Holiday Gift Books

Maine

Cafeteria Food; Fast Food

Happy 100th Birthday, Dear LHS

Giraffes, Etc.

A Monday Trip

Laconia High School, Etc.

Christmas Romance

National Potato Month

Globe

Preserving With Penny

Psychogeography

Bayswater Books

"Wild Girls"

Kitchens

Old Home Week

The Middle Miles

Bears, Horses, and Pies

Fourth of July 2023

Lucy and Willa

Frappes, Etc.

Still Springtime

In the Bedroom

Dried Blueberries

More Items of Interest

Fire Towers

Anne, Emily, and L.M.

Earthquake,Laughter, &Cookbook

Springtime and Poems

Cookbooks and Poems

Items and Poems

Two Pies

Audiobooks

The Cheeleader: 50th Anniversary

The Lot, Revisited

Penny

Parking and Other Subjects

Concord

Bird Food & Superbowl Food

The Cold Snap

Laughter and Lorna

Tea and Digestive Biscuits

Ducks, Mornings, & Wonders

Snowflakes

A New Year's Resolution

2022

Jingle Bells

Fruitcake, Ribbon Candy &Snowball

Christmas Pudding

Amusements

Weather and Woods

Gravy

Brass Rubbing

Moving Day

Sandwiches and Beer

Edna, Celia, and Charlotte

Sandwich Fair Weekend

More Reuntions

A Pie and a Sandwich

Evesham

Chawton

Winter's Wisdom?

Vanity Plates

2022 Golden Circle Luncheon

Agatha and Annie

National Dog Month

The Chef's Triangle

Librarians and Libraries

Clothes and Cakes

Porch Reading

Cheesy!

The Summer Book

Bears Goats Motorcycles

Tuna Fish

Laconia

More Publishers Weekly Reviews

Shopping, Small and Big

Ponds

The Lakes Region

TV for Early Birds; An April Poem

Family; Food; Fold-out Sofas

Solitary Eaters

National Poetry Month

Special Places;Popular Cakes

Neighborhood Parks

More About Potatoes and Maine

Potatoes

Spring Tease

Pillows

Our Song

Undies

Laughter

A Burns Night

From Keats to Spaghetta Sauce

Chowder Recipes

Cheeses and Chowders

2021

The Roaring Twenties

Christmas Traditions

Trail Cameras

Cars and Trucks

Return?

Lipstick

Tricks of the Trade

A New Dictionary Word

A 50th Reunion

Sides to Middle" Again

Pantries and Anchovies

Fairs and Festivals

Reunions

A Lull

The Queen and Others

Scones and Gardens

Best Maine Diner

Neighborhood Grocery Store; Café

A Goldilocks Morning_& More

Desks

Sports Bras and Pseudonyms

Storybook Food

Rachel Field

The Bliss Point

Items of Interest

Motorcycle Week 2021

Seafood, Inland and Seaside

Thrillers to Doughnuts

National Trails Day

New Hampshire Language

Books and Squares

Gardening in May

The Familiar

Synonyms

"Bear!"

Blossoms

Lost Kitchen and Found Poetry

More About Mud

Gilbert and Sullivan

St. Patrick's Day 2021

Spring Forward

A Blank Page

No-Recipe Recipes

Libraries and Publishers Weekly

Party; Also, Pizza

Groundhog Day

Jeeps

Poems and Paper-Whites

Peanut Butter

Last Wednesday

Hoodsies and Animal Crackers

2020

Welcome, 2021

Cornwall at Christmastime

Mount Tripyramid

New Hampshire Pie

Frost, Longfellow, and Larkin

Rocking Chairs

Thanksgiving Side Dishes

Election 2000

Jell-O and Pollyanna

Peyton Place in Maine

Remember the Reader

Sandwich Fairs In Our Past

Drought and Doughnuts&

Snacks

Support Systems, Continuing

Dessert Salads?!

Agatha Christie's 100th Anniversary

Poutine and A Postscript

Pandemic Listening & Reading

Mobile Businesses

Backyard Wildlife

Maine Books

Garlic

Birthday Cakes

A Collection of Quotations

Best of New Hampshire

Hair

Learning

Riding & "Broading" Around Sunday Drives, Again

The Passion Pit

Schedules & Sustenance

Doan Sisters Go to a British Supermarket

National Poetry Month

Laconia

Results

Singing

Dining Out

Red Hill

An Island Kitchen

Pandemic and Poetry

Food for Hikes

Social Whirl in February

Two Audiobooks & a Magazine

Books Sandwiched In

Mailboxes

Ironing

The Cup & Crumb

Catalogs

Audiobook Travels

2019

Christmas Weather

Christmas in the Village

Marion's Christmas Snowball, Again

Phyliss McGinley and Mrs. York

Portsmouth Thanksgiving

Dentist's Waiting Room, Again

Louisa and P.G.

The First Snow

Joy of Cooking

Over-the-Hill Celebration

Pumpkin Regatta

Houseplants, New and Old

Pumpkin Spice

Wildlife

Shakespeare and George

Castles and Country Houses

New Hampshire Apple Day

Maine Woods and Matchmaking

Reunions

Sawyer's Dairy Bar

Old Home Week

Summer Scenes

Maine Food

Out of Reach

This and That, Again

The Lot

Pizza, Past and Present

Setting Up Housekeeping

Latest Listening and Reading

Pinkham Notch

A Boyhood in the Weirs

The Big Bear

It's Radio!

Archie

Department Stores

Spring Is Here!

Dorothy Parker Poem

National Library Week, 2019

National Poetry Month, 2019/a>

Signs of Spring, 2019

Frost Heaves, Again

Latest Reading and Listening

Car Inspection

Snowy Owls and Chicadees

Sandwiches Past and Present

Our First Date

Ice Fishing Remembered

Home Ec

A Rockland Restaurant

Kingfisher

Mills & Factories

Squirrels

2018

Clothesline Collapse

Thanksgiving 2018

Bookmarks

A Mouse Milestone

Farewell to Our Magee

Sistering

Sears

Love and Ruin

A New Furnace

Keene Cuisine

A Mini-Mini Reunion

Support System

Five & Ten

Dining Out Again

Summer Listening

Donald K. MacDougall 1936-2018

Update—Don

Telling Don

Don's Health

Seafood at the Seacoast?

Lilacs

Going Up Brook, revisited

The Weirs Drive-In Theater

The Green and Yellow Time

Recipe Box and Notebook

Henrietta Snow, 2nd Printing

Food and Drink Poems

Miniskirts & Bell-Bottoms

The Poor Man's Fertilizer

The Galloping Gourmet

The Old Country Store

The entries below predate Ruth's transferring her use of Facebook. They appeared as very occasional opportunities to share what was of interest to her in and around her neighborhood.

2014 - 2017

Book Reviewing

April Flowers

April Snowstorm

Restoring the Colonial Theater

Reunion at Sawyer's Dairy Bar

Going to the Dump

Desks

A Curmudgeon's Lament

Aprons

Our Green-and-Stone-Ribbed World

Playing Tourist

2012-2013

Sawyer's Dairy Bar

Why Climb a MountIn

Penny'S Cats

Favorite Books

Marion's Christmas Snowball

Robin Summer

Niobe

Mother West Wind

Neighborhood Stoves

2008 - 2011

The Lot

Mother Goose

Colonial Theater

Aeons of Ironing

Our Canterbury Tale

Love it Here

Children of the Great Depression

Loads of Laundry

2004 - 2007

The Winter of Our Comfort Food

Rebuilding the Daniel Doan Trail

My Husband Is In Love with Margaret Warner

Chair Caning

The End of Our Rope

The Weirs

Frost Heaves

Where In the World is Esther Williams

The Toolshed

Sandwich Bar Parade

Lawns

2000-2003

That'll Do

Chipmunks and Peepers

A Fed Bear

Laconia HS 45th Reunion

Birdbrains

Drought

Friends

Wild Turkeys

Meadowbrook Salon

Lunch on the Porch

Damn Ice

A Male Milestone

1998-1999

Y2K

Fifties Diner

Glorious Garlic

Celebrated Jumping Chipmunk

Going Up Brook

Mud Season

BRR!

Vacation in Maine

Trip to Lancaster/Lisbon NH

Overnight Hike to Gordon Pond

Big Chill Reunion

Backyard Wildlife

Privacy Policy

This website does not collect any personal information. We do collect numerical data as to traffic to the site, but this data is not attached in any way to our visitors' personal or computer identities. Those clicking through to other websites linked from this page are subject to those sites' privacy policies. Our publisher, Frigate Books, maintains the same policy as this site; financial information submitted there is not shared with either Frigate Books or ruthdoanmacdougall.com.